Politics Down Under: How Does Voting Work?

Australians are required to vote in Federal, State and territory elections, but what does voting actually do? Why am I required to vote? How did marginalised groups gain the right to vote? And what are the pros and cons of our current voting system?

In Australia, eligible citizens or ‘electors’ are entitled to vote in Federal, State, and local government elections – either to express their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the political cycle and parties, or for that coveted democracy sausage. Yet Australia’s voting system is actually unique by global standards. For instance, Australian governments mandate that all electors are required to vote by law – and can be penalised for failing to do so. This is generally referred to as ‘compulsory voting’.

Likewise, Australia’s history of voting has been regarded as the gold standard for maximising civic engagement in the political process. For instance, did you know that most ballot papers used in elections across countries globally actually originate from Australia? Or that Australia pioneered in the women’s suffrage movements of the late 19th century?

History of Australian Voting

Before Federation in 1901, the Australian colonies (historically including Fiji and New Zealand) had become testing grounds for many developing ideas of liberalism throughout the 19th century. The early colonial legislatures of the Australian colonies (and by extension, in many democracies of the period) required voters to publicly declare their voting intentions when casting their ballot. These elections would occur in public spaces such as churches and pubs, which, as you can expect, could, and did, lead to political violence.

The Australian Gold Rush of the 1850s brought large influxes of migrant labour into the Australian colonies, especially from competing cultures, which inflamed social and political tensions. Issues such as mining licenses and Chinese migration to Australia caused scenes of political violence – including, most famously, the Eureka Stockade in 1854 – where gold miners rebelled against British soldiers, culminating in the deaths of 24 rebels.

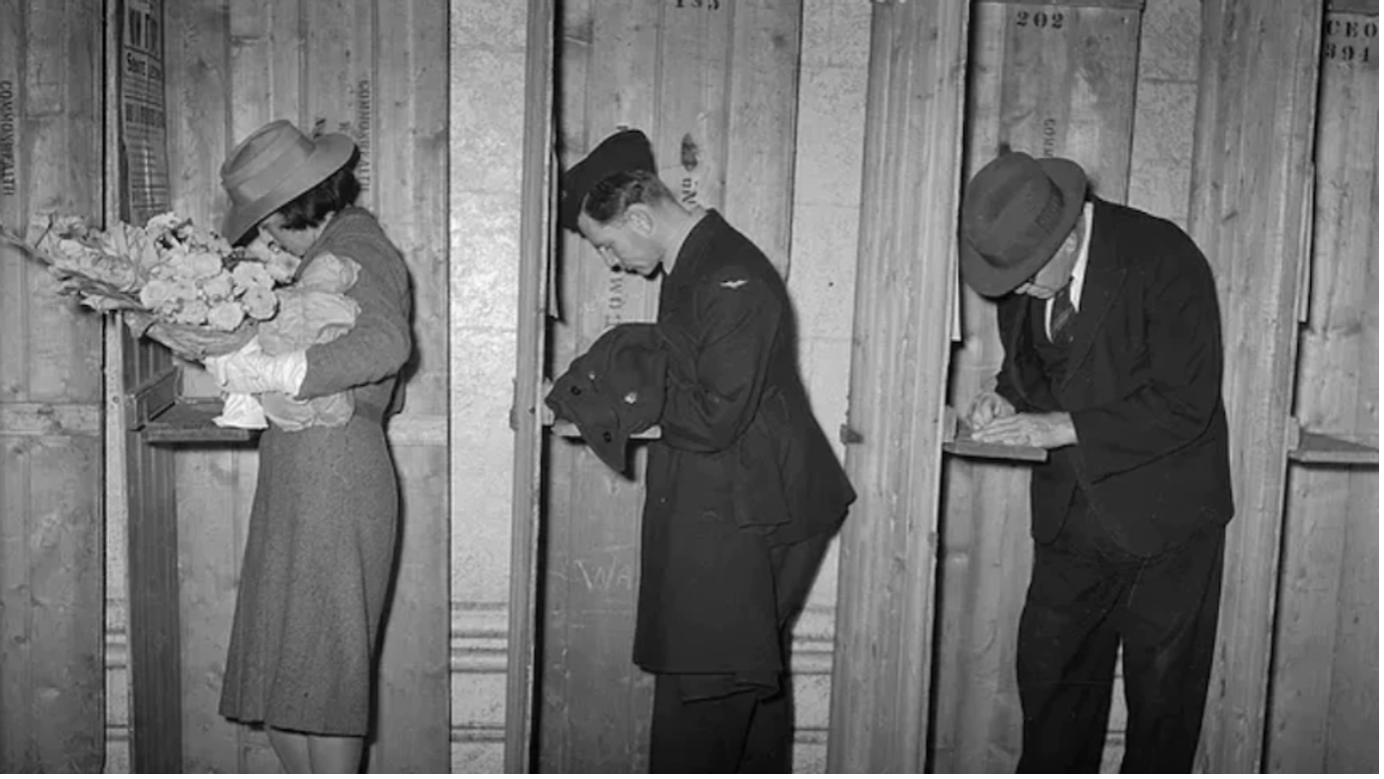

The next year, Victorian Legislative Council Member William Nicholson challenged the Victorian government’s opposition to electoral reform by successfully passing the first form of the ‘Australian Ballot’. The Australian Ballot, or secret ballot, enabled voters to privately cast their voting intentions via slips of paper, the purpose being to increase civic participation by reducing the threat of bribery and intimidation in politics. The secret ballot was expanded upon by South Australia a year later, when an additional box where electors could mark an ‘X’ beside their preferred candidate was added to ballots. The South Australian version quickly became the global standard, with the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States all incorporating the Australian Ballot into their voting systems.

Women and Indigenous Suffrage

The Australian colonies also received global attention during the late 19th century on the rising issue of women’s suffrage. The Women’s Suffrage Movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries developed in response to the changing social values brought about by the Industrial Revolution and the enlightenment of Europe’s middle and upper classes.

Early suffrage chapters developed in the New Zealand colony during the 1860s and later throughout continental Australia. Prominent New Zealand activist Kate Sheppard organised relentless campaigns, including popular petitions, to reform the law on suffrage to enable women to vote in elections. They argued that women provided greater moral clarity on issues such as health, education, and ‘Christian’ based social attitudes, and eventually succeeded in 1893 by making New Zealand the first jurisdiction to grant women the freedom to vote.

Other Australian colonies quickly followed suit, with South Australia’s own Catherine Helen Spence helping campaign for reforms to suffrage laws in South Australia. Following Federation, the Commonwealth government passed reforms to the Electoral Act in 1902 to grant women the right to vote in federal elections - although women in Victoria were excluded from voting in state elections until 1908.

The campaign for Indigenous suffrage was far more complex however, with prominent campaigners Joe McGuinness and Oodgeroo Noonuccal fighting in a much more drawn-out campaign. Only South Australia allowed Indigenous Australians to vote in elections, as long as they met the standard property qualifications established for electors – known as property voting. This model continued after Federation on a state level – although New South Wales and Queensland only allowed this decades later – with Victoria abolishing the freedom altogether in 1934. In 1949, the Commonwealth government granted suffrage to Indigenous Australians who had fought in World War Two, but Indigenous turnout was generally low across Federal and State elections. In 1962, the Commonwealth Electoral Act was amended to enable Indigenous Australians the freedom to vote in elections but was only made compulsory in 1984.

Compulsory Voting

In the early days of Federation, Australia's first political leaders from across the political spectrum envisioned establishing a society that valued civic engagement in the execution of government. Australia's second Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, was a major proponent of expanding civic engagement and often campaigned for greater political engagement with voters – however, despite claims in other online publications, it is actually unclear whether he endorsed the idea of compulsory voting himself.

In 1911, Australian Prime Minister Andrew Fisher did make enrolment mandatory across federal elections in what is viewed as the precursor to compulsory voting. The first instance of compulsory voting occurred in 1915; Queensland was entering an election where the incumbent Liberal Government feared Labor's ability to get its base out to vote. In an attempt to thwart Labor, the Liberals passed compulsory voting in an effort to equalise the broader vote to win the election (ironically, the Queensland Liberals would still lose this election).

Compulsory voting, however, became subject to a nationwide debate in the 1920s. In the 1919 Federal Election, more than 71% of voters turned out, but only three years later in 1922, less than 60% showed up. This severe decline was likely caused by the end of the First World War, the Spanish Flu, the rise of the Country Party (now National Party), and voter apathy following the political division that plagued Australia's Federation and three-party system. While a 60% turnout might be regarded as good by modern standards in some countries, many first-generation Australian political leaders were horrified by the results, seeing it as a failure of civic engagement. Australia's then Nationalist Government, led by Prime Minister Stanley Bruce, intervened by accepting a private member's bill by Tasmanian Nationalist Senator H.J.M. Payne to make voting in federal elections compulsory. This worked, with Australia's turnout in the 1925 Federal Election immediately rising to 91%. Since then, compulsory voting has meant that most elections have seen turnouts roughly above 90%.

The adoption of compulsory voting was a catalyst for states to also adopt the same reforms. Victoria introduced compulsory voting a year later, New South Wales and Tasmania in 1928, Western Australia in 1936, and South Australia in 1942. Both the Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory were given compulsory voting alongside their self-governments in 1978, and 1989 respectfully. Compulsory voting has since become a matter of national pride for many Australians, viewed as an effective way to enable greater civic engagement and give all Australians a stake in the political process.

How Voting Works in Australia

The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918, under section 245(1), states “it shall be the duty of every elector to vote at each election”. Under the Act, the actual duty of the elector is to attend a polling place, have their name marked off the certified list, receive a ballot paper and take it to an individual voting booth, mark it, fold the ballot paper and place it in the ballot box.

It is not true that it is only compulsory to attend the polling place and have your named marked off, and this has been upheld in numerous legal decisions.

As voting is compulsory, electors are given a number of ways to cast their vote at an election, including postal voting, pre-poll voting, absent voting, voting at Australian overseas missions and voting at mobile teams at hospitals, nursing homes and in remote communities, alongside voting at a polling place in their electorate.

Because of the secrecy of the ballot, it is not possible to determine whether a person has completed their ballot paper prior to placing it in the ballot box. It is therefore not possible to determine whether all electors have met their legislated duty to vote. However, it is possible to determine that an elector has attended a polling place or mobile polling team (including postal vote, pre-poll vote or absent vote) and been issued with a ballot paper.

There are currently 32 countries with compulsory voting of which 19 (including Australia) enforce. This includes Argentina, Belgium Brazil, Greece, Mexico, Singapore, Switzerland, Turkey, Italy, Netherlands and other nations.

Pros and Cons of Compulsory Voting

Despite the objective success of compulsory voting in making the Australian public engaged during election cycles, the actual practice has been regarded as relatively controversial by domestic critics and in overseas democracies.

Liberalism, which underpins most democracies globally, has a paradoxical relationship with compulsory voting, whereby liberalism emphasises empowering the population to be free to engage in the political process, while also emphasising limited government involvement in the process of voting – e.g., protecting the freedom to choose. This has been subject to centuries of legal and political debate.

Advantages of compulsory voting include understanding voting as being a necessary part of active citizenship, increasing the legitimacy of elected representatives by giving them a clear public mandate to govern, requiring greater civic education for the public, political candidates having to campaign to wider sections of the electorate, and keeping the system responsive to voter needs.

Disadvantages argued by opponents include that citizens should have the ability to choose to vote, that it reduces the legitimacy of elected representatives by enfranchising ill-informed voters into the political process, that Australians, despite compulsory voting, are no more politically educated than voters in the United States or United Kingdom, that marginalised communities might vote for candidates who they believe do not represent them, and that the political system becomes elitist in its responsiveness.

In overseas democracies, compulsory voting has become subject to partisan politics, especially in the United States and United Kingdom – where parties argue increased voter turnout benefits left-wing parties over right wing parties or enfranchises misinformed voters.

But Australia is a testament to demonstrating both these arguments as flawed. Australian academics and even politicians, have argued that compulsory voting has enabled all Australians to hold a critical stake in our nation’s governance, and has allowed a town square of ideas to develop. Perhaps this is something other nations should consider when reforming their own political systems.