Picture this: Living with a ‘blind mind’

Can you picture something that’s not in front of you?

Can you imagine how something tastes, or how someone you’re not with talks?

Everyone thinks in a slightly different way, and thus learns in a slightly different way. We all know how we ourselves think, but if we were ever in someone else’s head it is likely they would think so differently that we wouldn’t be able to understand. Most people can imagine the five senses in their head, and some think in that way too – albeit mostly with visual creations. Most can imagine the taste of something, or picture how something looks. Some can recreate the feeling of a scrape on their knee, or the sound of someone’s voice. Some, on the other hand, cannot imagine any of the senses, and have a neurocognitive phenomenon known as aphantasia, whereby the imagination of these senses is non-existent in their minds. I am one such aphantasic, and can’t imagine any of my senses.

There are different levels of aphantasia, and different types. It primarily manifests in visual mental creation. If you concentrate, can you picture a yellow balloon? Can you then picture the balloon with a string attached to a gingerbread house? Some people can see this very vividly, some see a faded picture, and some can’t at all. For me, I read a description of the balloon attached to the gingerbread house, but I don’t actually visualise a picture. Aphantasia is commonly referred to as a ‘blind mind’, and everyone with aphantasia has some level of ‘blindness’ in their minds. Some, in addition, also have a ‘deaf’ mind, or a ‘tasteless’ mind (Arnold and Bouyer, 2024).

My aphantasia presents itself in the senses, so instead my mind is laid out like a book I am reading. I don’t picture something, I read a description of it, and work with that. Because a book doesn’t give you an experience of how something smells, tastes, or feels I also can’t imagine those senses. Some other people with aphantasia, on the contrary, can’t visualise things, but can imagine a smell, or can only visualise things and no other senses are used. The number of forms of aphantasia are limited solely by the number of people who have the phenomenon.

Because everyone presents a different form of aphantasia, and aphantasia affects the way you think, learning for everyone is very different. This imagination difference alters how one retains information, and how they understand what they need to learn in the first place. I noticed this in physics class, because I can’t imagine how an object would move; I need very specific description of a phenomenon in order to understand it, and this usually means analogies that I could compare to something I already understand.

The reason behind this characteristic is still not fully understood, but there have been theories. Derek Arnold, a professor in the School of Psychology, and Loren N Bouyer, a PhD student studying neuroscience at the University of Queensland, have theorised that aphantasia is, at its most basic, “when activity at the front of the brain fails to excite activity in regions towards the back of the brain” (Bouyer and Arnold, 2024). Many researchers, having said this, are at pains to reinforce that aphantasia is not a disability, merely a characteristic, like right- or left-handedness (Cleveland Clinic, 2021).

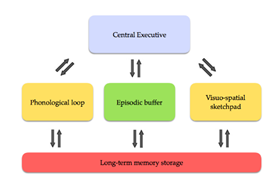

Another way of thinking about aphantasia is through the working memory model posed by scientists Baddley and Hitch in 1974. The working memory model has three main levels: the central executive that oversees everything; the phonological loop, episodic buffer and visio-spatial sketchpad; and the last level is the long term memory storage. The phonological loop contains the articulatory control system (inner voice) and phonological store (inner ear), which work together in processing what you hear, what sounds you remember, and the voice in your head when you think. The episodic buffer works to create snapshots of ‘episodes’ of flashback memory, and make use of memory of all senses, however it isn’t very clear and doesn’t capture the full moment. The visio-spatial sketchpad is your memory of anything visual (inner eye) and spatial awareness in general. It helps you remember where you might have left something, how to navigate your house, or what something looked like (InThinking IBDP Textbook, 2023).

Aphantasia, within the working memory model, comes into play when one of the components doesn’t work properly. Everyone’s work slightly differently, and some work less than others. For me, my articulatory control system (inner voice in my head) works fine, but my phonological store can’t allow me to hear the sound of someone’s voice in my head. My visio-spatial sketchpad doesn’t work in visualising how something looked, but I can remember where I left something. Because everyone is slightly different, there isn’t really a generalised model that we can use, but researchers are working on it.

There are two ways of getting aphantasia: it being congenital or acquired, primarily in response to an occipital lobe injury (Cleveland Clinic, 2021). When congenital, there is no need for aphantasia to be treated, however there are possibilities of people learning to visualise (Arnold and Bouyer, 2024). When acquired, the aphantasia is a result of injury, and that injury should be treated, but speak to your doctor should you believe that something could be wrong.

The implication of this therefore is that especially in classrooms, teachers need to be able to cater for different levels of imagination. Students also need to be able to learn to identify the manner in which they learn and understand best, to inform the teacher for them to then try to incorporate into their teaching.